An economy’s growth is like sailing on two boats tugged to each other. On one side is the supply or the production of goods and services. GDP, or gross domestic product, is the value the production process adds. On the other side, there is demand or expenditure for purchasing these goods and services from the market. Both the supply and the demand boats must move in tandem. If supply proceeds slower than demand, prices rise, leading to inflation. If demand falls behind, firms will be left with unsold inventories, which may lead to cuts in future production, job and income losses, and a worsening cycle of demand and growth slowdown.

The demand or aggregate expenditure in an economy comes from four sources. First is private consumption, which is the sum of expenditures by all individuals on items such as food, clothing, and mobile phones. Second is private investment, which is the amount spent by firms and households on installing new machines and constructing new factories or residences. Third is government expenditure, for consumption and investment. The former refers to the money spent on day-to-day government operations, including paying salaries to officers, teachers, doctors and others attached to public institutions. Fourth is net exports or exports minus import of goods and services while engaging in trade with the rest of the world.

Editorial | Losing momentum: On slowing consumption demand

Investment and its multipliers

Among the sources of demand, investment stands out for its ability to create ‘multiplier effects’. That is, an increase in investment of ₹100 could increase the economy’s overall demand and GDP by more than ₹100 — let us say by ₹125, with the multiplier being 1.25. Consider, for instance, public investment in building a new highway network. The incomes received by workers and firms involved in the road construction project will generate fresh demand in the economy. But that is not all. The highways will trigger the establishment of new shops and create opportunities for new industries, all of which translate into a much bigger expansion of aggregate demand. The multiplier effect will depend on the nature of the investment and the state of the economy. The multiplier from an investment in a railway line is likely higher in an underdeveloped district than in a region with a well-developed transport network.

Compared to investment, the multiplier effect arising from increased consumption is much weaker. If incomes increase, consumption expenditures also increase, but the relation does not work strongly enough in the reverse direction. A rise in consumption cannot lift incomes as much in the rest of the economy. Therefore, according to Keynesian economists, consumption is a passive component of aggregate demand.

Indian and Chinese experiences

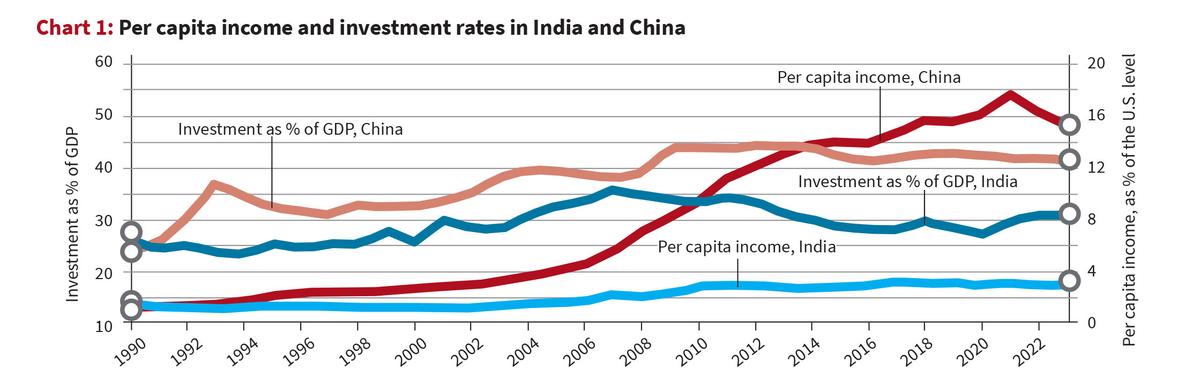

In the early 1990s, the per capita incomes of India and China were almost the same. Both countries were equally poor, with the average income of an Indian or Chinese resident being approximately 1.5% of the average income of an American. But by 2023, China’s per capita income has grown to five times as high as the Indian level (2.4 times as high if purchasing power differences between the two countries are considered). As a proportion of U.S. levels, the per capita incomes of China and India were 15% and 3%, respectively, in 2023 (Chart 1). The speedy growth of incomes in China has been led by investment.

GDP = Value added in the production of all goods and services = C + (I+ Ig) + Cg + E — M

C =private consumption; I = private investment; Ig = investment by the government; Cg = government consumption; Cg + Ig = G or government expenditure; E = exports of goods and services; M = imports of goods and services.

China’s investment rates have been significantly higher than India’s from the 1970s onward. In 1992, investment as a share of GDP was 39.1% in China compared to 27.4% in India, even though the per capita incomes of the two countries were nearly equal. The gap in investment rates between India and China narrowed during the first half of the 2000s, with India’s investment rate climbing to 35.8% in 2007. However, the two countries responded to the global financial crisis of 2007-08 and its aftermath in starkly different ways. The investment rate took a big hit in India, especially after 2012. However, China battled its economic challenges with considerable expenditure, primarily through its state-owned enterprises, in areas such as infrastructure, advanced manufacturing, renewable energy, and artificial intelligence. By 2013, the investment rate rose to 44.5% in China but dropped to 31.3% in India. In 2023, these rates were 41.3% and 30.8%, respectively, for China and India (Chart 1).

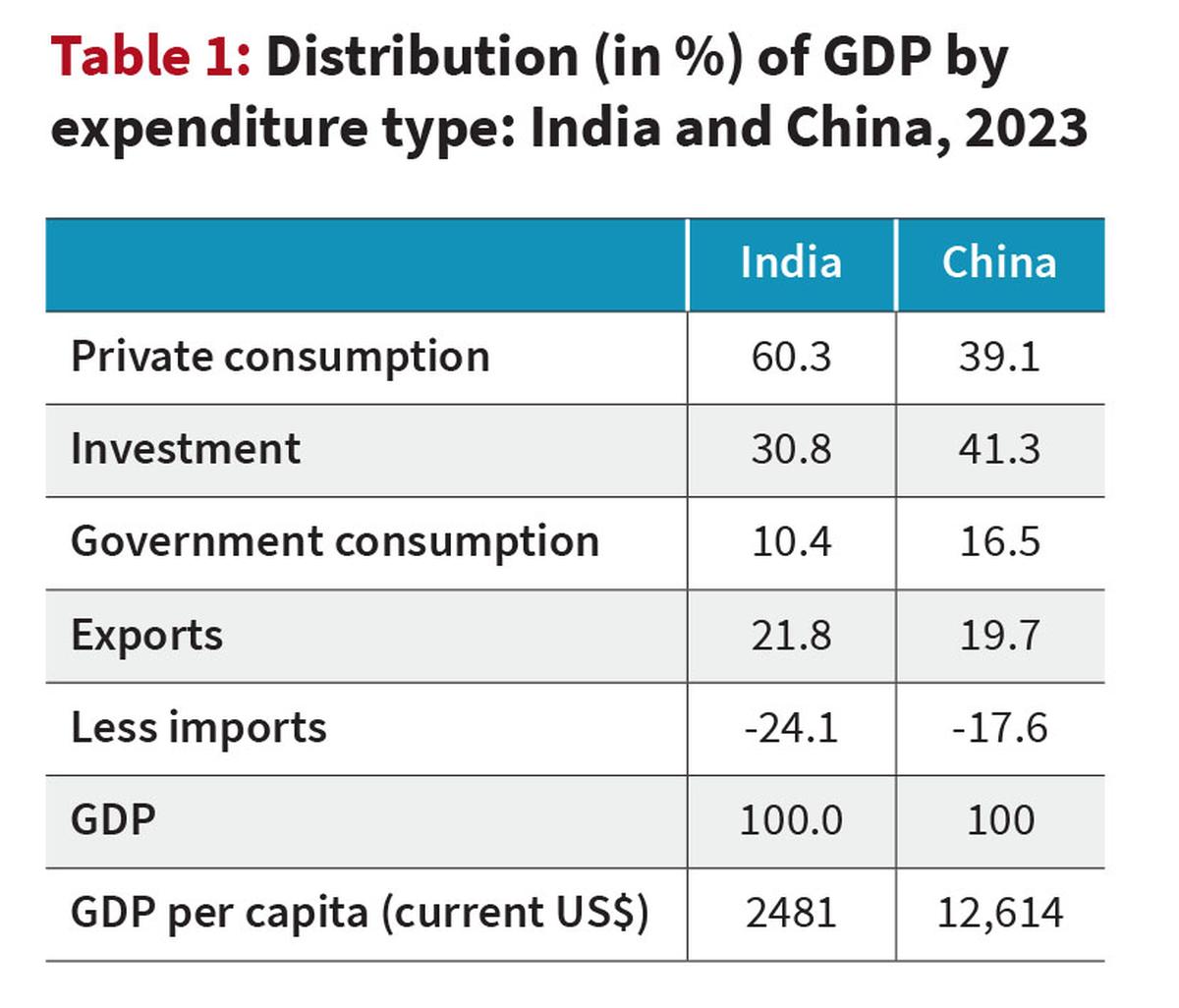

India’s economic growth over the last decade has been driven mainly by expanding domestic consumption expenditures. In 2023, consumption as a share of GDP was 60.3% in India compared to 39.1% in China (Table 1).

The dominance of consumption in India’s GDP structure is mainly due to the weaknesses of the other components of aggregate demand in the country. The shares of investment and government consumption expenditure are relatively low. India also has a trade deficit, with its import of goods and services being larger than its exports, reducing domestic demand.

Economic growth driven by consumption is not only slower than investment-led growth, but it also aggravates inequalities. The growth of jobs, incomes, and consumption has remained depressed for many Indians, and they will be left behind.

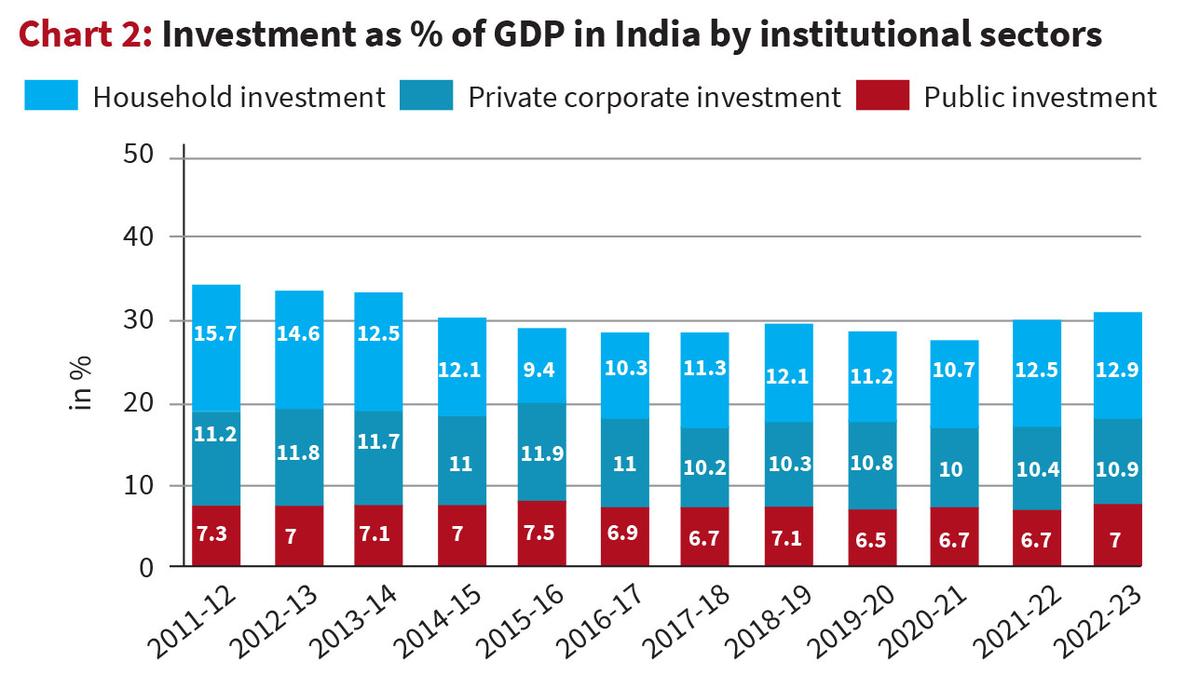

There has been a stagnation in the growth of investment by the public and private corporate sectors in India (it is too early to say if the marginal improvement in investment in 2022-23 is here to stay) (Chart 2).

Note: Investment is gross fixed capital formation by the private sector and the government combined.

The only segment that has shown some vitality is household investment, especially in residential buildings, and that too during the early 2010s. The continued reluctance of private capitalists to spend more in the economy is a sign of their sagging ‘animal spirits’. In times like these, the government needs to step in with its investments, particularly in critical sectors, to boost private sector confidence and help spread the benefits of growth to the broader population.

However, the government has not shown its resolve, including in the latest Union Budget, to provide an investment boost to the Indian economy. Instead, the tax concessions and the unwillingness to significantly raise government spending indicate a preference for a low-growth trajectory pulled by the consumption of the middle and upper classes.

Jayan Jose Thomas is a Professor of Economics at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) Delhi.

Published – February 21, 2025 08:30 am IST